Egton Gooseberry Show

Words by Cameron Hill

A gooseberry does not have the easy looks of some of its cousins, the jewel-like colour of a raspberry or blackberry. They seem a little mundane, a little muted. But, if you watch them long enough, the patterns and distinctions in them start to appear: green-cream veins over-lacing jade-green depths, short hair-spikes of green emerging from smooth yellow-green skin, berries of deep burgundy reds and those of soft sunburnt-red blushing on ripe-green. There is a whole universe of these berries; variations with names like the Montrose, the Lord Derby, Rough Robin, Green Ocean, the Belmarsh and the Bonny Lass. From variety to variety, they can be soft-sweet or tart, almost bitter. When grown to a good size, biting into one can be plum-like, the soft flesh pulling away to show the world inside. Even in berries grown from the same variety, taken from the same bush, tended by the same grower, you can read these subtle, deep differences; these tart-sweet traces of the complexity of the world and what we have made of it.

For two hundred and twenty-one years, the members of the Egton Bridge Old Gooseberry Society have come together to show and measure these fruits here at their yearly Gooseberry Show. The challenge is deceptively simple, grow the biggest berries.

Found just off the North Yorkshire Moors, Egton Bridge is a small, loose village set in the base of the glacier-carved valley that follows the River Esk. Car traffic is minimal. There are a series of Californian Sequoias, their fibrous bark thick with the years in it. Sound feels dampened by the wood-lining of the valley, with this long avenue of bird-flown sky stretching above you. There is a still calm to this place, its rhythms like the languid meander of the river it holds to.

Since the nineteen-sixties the show has taken place at the village’s primary school; a small, slightly squat building overshadowed by the church it is attached to. This morning, there is a solitary speaker playing brass band music on a loop in the entrance/netball court/playground underneath that stretching blue, wood-lined sky. The classroom the show takes place in is slightly tattered (it is about to be remodelled) with pale green walls and ‘Let your light shine’ stuck up above a door in friendly gold letters. For today, it has been remodelled as a berry exhibition space, with information boards full of the history of the society dominating one side of the room and large wooden tables arranged into one long central row and covered with soft, white cloth.

The berries have to be here on one of these tables before noon, and they arrive in a perfect variety of cases. One is sturdy and metallic, looking like its ready to protect the berries from anything short of a direct bomb hit. There is an old Rover Assorted Biscuit tin, paintwork scratched and marked by repeated showings, repeated drives between berry bush and weighing scales. A lot are just egg cartons. The prizes are just as eclectic and warmly practical: a teapot, multi-purpose pressure sprayers, a bug hotel, Fish Blood & Bone (Natural Feed for a Healthy Garden).

At the end of the row of tables, beneath that friendly gold sign, the judges are arranged around the committee’s lovingly maintained Avery scales, taking turns to weigh these berries in the traditional units of Drams and Grains. It is hours before the crowds arrive and the room is all rhythmic calm: watching and weighing, note-taking, discussing, weighing and watching as the day wakes up. The conversation ebbs and flows between earnest debate and jokes, the repeated refrain of ‘there’s always next year’ like a warm, well-handled mantra passed on through the group from crop to crop, show to show. There is talk of farms and sons inheriting businesses, conversations whittled from this deep, growing knowledge of the area – all interlaced with the names of berry variants – Newton, Woodpecker, Belmarsh – a green-tongued code of varieties and weather and technique, of care and hours and days given to these fruit.

Trevor, one of the society members, has grown gladioli that are glowing colour in the room, vases of them lined up down the middle of the white-cloth coated display tables. He was a national champion with these flowers in 2016 and you can see why. They are perfect in form and colour - the flowers on one grouping an outer purple blending into a soft pink, the other all hues of peach unfurling from the tight, fresh green of the stem and buds. They are flanked by two rows of yellow plastic plates with white doilies underneath and interspersed with thin wooden pedestals. This is where the berries will be presented: thirteen from each grower on these plates, the lofty pedestals reserved for the elite prize winners.

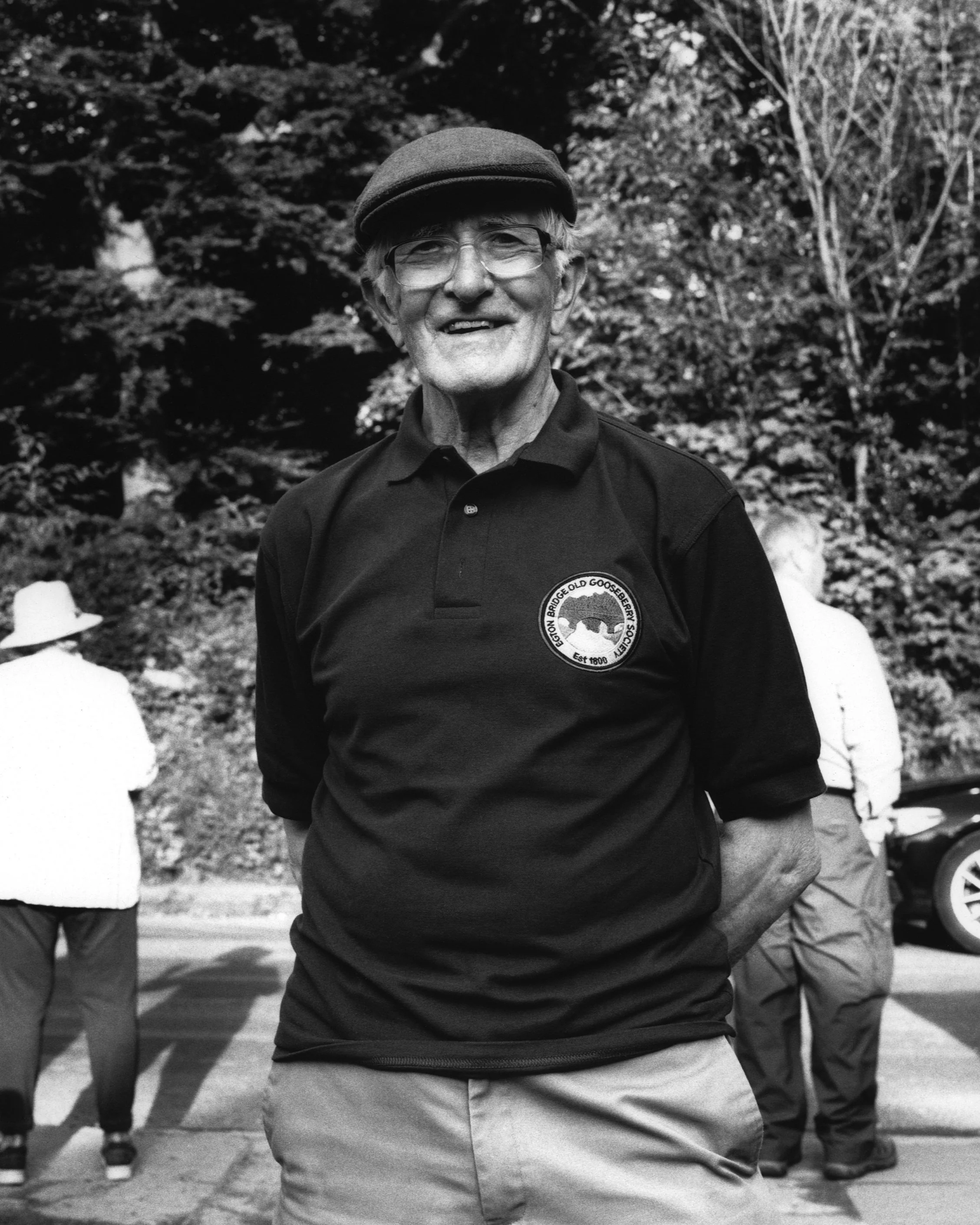

Growing gooseberries of this size is a complicated task. Bryan Nellist, grower of this year’s Champion Berry (the biggest in show, by 1/200th of a gram) and former world record holder, has been growing berries competitively for sixty-five years. A generous figure with an easy smile, he well knows the commitment and consistency that is required to succeed here.

He told me that the very first essential is starting with cuttings from other grower’s bushes, rather than from garden centres or from seeds. Gooseberry growing is a process of community and of continuity. Then, it is not just a question of taking these cuttings from their pots and sticking them in the ground. When a bush is fully established, its roots can extend for four or five feet, stretching out into the dark earth around it. So, the whole area needs to be well prepared. Dig manure or compost throughout it all, make the soil rich and ready.

This compost you have now dug into it will help keep the moisture in but make sure the area is not too wet, or too dry. And the bush’s feeding roots are shallow, so we need a ‘good thickness of rotted muck or compost’ spread over the surface of the area as well. If these gooseberries are going to be competition winners, they need to be pampered.

You want a steady, well-timed Spring (not too early or they will come on while the weather’s still a bit ropey, not too late or they won’t have enough time to grow). Then, a sun-lit procession of a Summer. They need to peak in size at just the right time. Coax their best performance out of them. It is no use having a prize-winning berry weeks after a show.

Pray for weather that is gradual and consistent. If a period of heavy rain is followed by a lot of sun, then a ripening berry can burst. Seed-guts and a year of effort splattered on the ground. The cold can hurt your crop as well, with frosts damaging the growth and lower temperatures meaning fewer pollinating insects meaning fewer berries.

You have to be prepared for these dangers. Bryan’s berries are protected from the rain and heat by a system of waterproof covers and umbrellas. If a cold spell is on the way, they are covered with fleece every night to keep them warm and safe until the morning sun comes to thaw the frost. These berries are delicate souls. And you can only worry about their future, looking toward a British climate that will bring increasingly erratic weather, oscillating between heavier rain and stronger heat, and a collapsing insect population.

Finally, be aware that we are not the only species around here who likes a gooseberry. Wasps will come for them. Mildew will creep unseen. All the bugs that crawl the earth will want a taste. Bryan’s crop is protected first by tin sheets about two feet high, then another eighteen inches of wire netting and then a railing over the top. This construction protects them year round. From June, he will add onto this a net over it all to keep circling birds out (blackbirds are the worst). Despite all of this, Grey Squirrels will still find a way to break in, climbing poles and gnawing holes in the netting.

Growing these berries to this size is a feat of sheer, cyclical commitment. It is essentially a year-round task that Bryan has been performing every single year for the sixty-five years since he returned from National Service in 1956.

The time it takes to reach his level of performance – he has won the championship six times - is astounding. It takes decades to develop the right ‘stock’; watching your bushes take their time, year after year, knowing that with your dedication and patience they will bear fruit, that together you will make something. A few smaller wins aside, it was not until after he had retired in the late nineties that he started winning the big prizes. Graeme Watson, who won the most overall points for his berries this year and has been something of a force in recent competitions, was growing berries for fifteen years before his first prize. He described it in passing as like raising children or pets – a labour of time, attention, care.

It is a journey of marginal gains, year after year of the steady optimisation of growth. There is a need to learn your way, to grow and develop in step with your bushes through season after season of dialogue with sun, rain, earth; the whole climate and landscape coming together in these little and not so little berries. This is the raw complication of such humble fruit.

Talking to these growers reminds you that food is not instantaneous, that it is a process of labour and attention. What first seems like the event’s quaintness is just the evidence of an older countryside in decline - an increasing disconnect between people and landscape, a widening chasm between people and the realities of food. These berries are the fruit of decades of nurturing the earth. The joy of small, personal things. In a culture of mass-produced food grown on the other side of the world and delivered by multi-national corporations – strawberries on shelves year round, bland tomatoes shipped to our supermarkets in the dead of winter – there is something so satisfyingly interdependent about this relationship with the seasons and the area, a reminder that you are connected to and reliant on the world.

The earliest record of this Gooseberry show is in 1800, meaning it is the oldest surviving one in the country. When people first started weighing gooseberries here, Napoleon had just taken control of the French government, the construction of The White House had just been finished and Beethoven had just performed his first symphony. And each year since, the berry bushes of this river-tracing valley have taken root and given fruit. You can see markers of the age of the event scattered around the room. Black and white photos show prize winners standing proudly. Old records and Growers Registers are pinned to the walls, a kind of thumb-tacked legacy literature. There is a photo from 1937, of men with serious faces, strong moustaches and three-piece suits weighing gooseberries on the same oil-dampened Avery scales that are used by the committee today. To look at the scene this year and that photo you are seeing how still and thin time is here, how close to the past this continued tradition brings you, the half-remembered names and faces living on in these shared motions of delicate weighing and the year after year growth and harvest - this older countryside, continuing on in spite of everything.

The society is understandably eager to spread the word, to get others snagged on these bushes as they first were. And there seems to be a good age spread in the crowd; the people a mix of some older faces and kids milling about with more enthusiasm for the tombola and cake than these arranged plates of berries. Some are just people who were passing by – families on their staycations, people drifting in off the Coast to Coast – but there is a steady core who seem to come here year on year, decade on decade, as dependable and cyclical as the seasons.

Potted young bushes that were grown from cuttings from the committee’s own plants are available to buy and apparently sell-out every year. It is encouraging seeing them proudly escorted out the front door, being taken away to family gardens and allotment strips. They will stretch out their roots around the Esk valley and further away; plant living on in plant, garden connected to garden, grower to grower, a community tied together by root networks. In these small arboreal legacies grows the hope that these two hundred years of roots will keep developing, keep thriving.

Bryan has changed the varieties of berries that he has grown over the years. He has seen a lot of more modern variations (often coming from the rival shows in Cheshire) appearing on the scene. But he has moved and adapted with the times, continuing and competing as the harvests and shows come and go.

One of his great ambitions has been to develop his own named variety of gooseberry. And so, after being awarded the Guinness World Record in 2009, he kept the seeds from the winning fruit in the hope that they would develop and grow well. ‘You don’t know what you’re going to get, you just take pot luck’ and the berries grown from these seeds have to reach a certain weight within two years if they are going to be recognised as their own variety, their own berry.

They made size, and he christened them Kingfisher. Kingfisher gooseberries are the product of his sixty-five years of care and attention, a lifetime’s worth of existence in a place and a love for something. These berries will live on in the cuttings of other committee members. Their descendants will take root in fertile patches of earth and will give sun-fed, green-veined fruit as the seasons roll into years, and the years keep on rolling into tradition.